Martial Virtue: Wisdom From Jet Li's Fearless

Combat Sports and the Loss of Martial Virtue

What happens when a man becomes unbeatable and discovers that winning is not the same as being whole?

Jet Li’s Fearless tells the story of Huo Yuanjia not as a legend polished by victory, but as a man shaped by consequence. At the height of his fame, Huo is the most feared fighter in China. Crowds gather to watch him dominate challengers. His name becomes synonymous with strength, prestige, and spectacle.

Still, something in him remains unfulfilled.

Huo’s fists win fights, but they do not bring peace. Each victory sharpens his reputation while hollowing his center. What appears as confidence is driven by insecurity. What looks like honor is entangled with ego. The art that should have cultivated his character becomes a stage for proving worth.

Then everything collapses.

What follows is not the familiar arc of revenge, nor redemption through greater violence. Instead, Fearless asks a far rarer question in modern entertainment:

What if the highest form of strength is learning when not to fight?

To understand Huo’s journey, one must understand the idea that ultimately defines it: Wu De (武德).

And to understand Wu De, we must first understand the story Fearless is telling.

If you have not seen the film yet, I recommend watching it before continuing.

What follows contains spoilers.

The Story of Fearless

Fearless follows the life of Huo Yuanjia, a real historical martial artist living in China during a period of national humiliation and foreign encroachment.

Huo begins as a talented but insecure young fighter who is forbidden by his father to train. Driven by a need to prove himself, he trains in secret and eventually becomes an exceptional martial artist. As an adult, he challenges and defeats other fighters in public matches, quickly earning a fearsome reputation. His victories bring fame, wealth, and admiration, but they also bind his identity entirely to winning.

At the height of his success, Huo provokes a rival martial artist in a fatal duel. In retaliation, his enemies poison his family, including his mother and young daughter. The consequences of his pride and violence return to him magnified. Devastated by guilt and grief, Huo abandons his old life and disappears.

Overwhelmed by grief and collapse, Huo wanders into a rural farming village. There, stripped of status and identity, he lives as an ordinary laborer. He works the land, eats simply, and lives according to natural rhythms. Over time, his body heals and his mind quiets. Martial arts cease to be something he performs for recognition and become something he lives through alignment, restraint, and presence.

Years later, Huo returns to Shanghai to find Chinese fighters publicly humiliated by foreign competitors. Instead of reclaiming his former reputation, he helps establish the Jingwu Athletic Association, dedicated not to spectacle or challenge fighting, but to discipline, education, and moral cultivation.

Huo enters an international tournament not to dominate, but to demonstrate dignity and conduct. He defeats his opponents without cruelty or humiliation, showing respect even in victory. Before the final match, he learns that he has been poisoned and will die regardless of the outcome. Knowing this, he chooses to fight anyway, not for glory or survival, but to embody restraint, courage, and moral clarity.

Huo dies, but his death is not framed as defeat. It is the completion of his transformation. He leaves behind not a legacy of domination, but a standard of martial virtue that transcends winning.

The Ordinary as the Path Back to Virtue

One of the clearest ways to understand Huo Yuanjia’s transformation in Fearless is through a short poem by William Martin, from Tao De Jing of Parenting:

At first glance, this poem appears to be about parenting. In truth, it is about cultivation. And few films illustrate this principle as cleanly as Fearless.

Huo’s early life is defined by striving for the extraordinary. He wants to be unbeatable. He wants recognition. He wants to prove his worth through dominance. His victories are spectacular, and they are admired. But they come at a cost. The more extraordinary his fighting becomes, the narrower his inner life grows.

This is exactly the danger the poem warns against.

Striving for the extraordinary feels noble. It looks like ambition, excellence, even virtue. But when striving becomes identity, it pulls one away from rhythm, proportion, and self governance. What appears admirable on the surface quietly erodes the center.

Huo’s collapse forces him into the ordinary.

After tragedy, he does not seek a greater opponent or a higher stage. He disappears into farm work, simple meals, shared labor, and seasonal time. He tastes food again. He listens. He slows down. He grieves without performance. He relearns what it means to inhabit a body rather than display it.

This is not retreat.

It is an awakening.

The poem’s insistence on the ordinary mirrors this perfectly. The wonder of tomatoes, apples, pears. The grief of loss. The pleasure of touch. These are not distractions from greatness. They are the conditions that make virtue possible.

Only after Huo has returned to the ordinary does Wu De re emerge.

When he returns to the public stage, his fighting is no longer extraordinary in the way the crowd expects. It is quieter. More restrained. More precise. He humiliates no one. He seeks no spectacle. His conduct carries more weight than his strikes.

Huo does not regain greatness by chasing it. He regains it by becoming whole.

The extraordinary does take care of itself.

This is the deeper Daoist truth the poem and Fearless share:

The extraordinary that is pursued directly corrodes the soul.

The extraordinary that emerges from an ordinary life is stable.

True Wu De does not arise from striving alone.

It arises from alignment.

And that is why Huo Yuanjia’s journey endures. Not because he became unbeatable, but because he learned how to stop needing to be.

What Is Wu De (武德)?

Wu De is usually translated as martial virtue.

Not morality imposed from rules or reputation, but character revealed through power.

In traditional Chinese martial culture, Wu De is the ethical gravity that governs the use of force.

It answers a simple but demanding question: What kind of person do you become as your ability to harm others increases?

Wu De exists because skill alone is dangerous. A practitioner who can dominate others but cannot govern himself is considered incomplete.

Martial arts were never meant merely to defeat opponents. They were meant to cultivate the person wielding them.

At its core, Wu De has two inseparable dimensions:

Outer virtue

Respect, restraint, responsibility toward others

Inner virtue

Humility, self control, emotional regulation, freedom from ego, hatred, and the hunger to dominate

A person with Wu De may be fully capable of violence and yet choose restraint. Not because he is weak, but because he is no longer ruled by fear, pride, or the need to be admired.

Wu De does not mean avoiding conflict.

It means mastery that does not corrupt.

It is the difference between being feared and being respected.

Between winning and being worthy.

Between strength that escalates and strength that stabilizes.

When Excellence Turns Against the Self

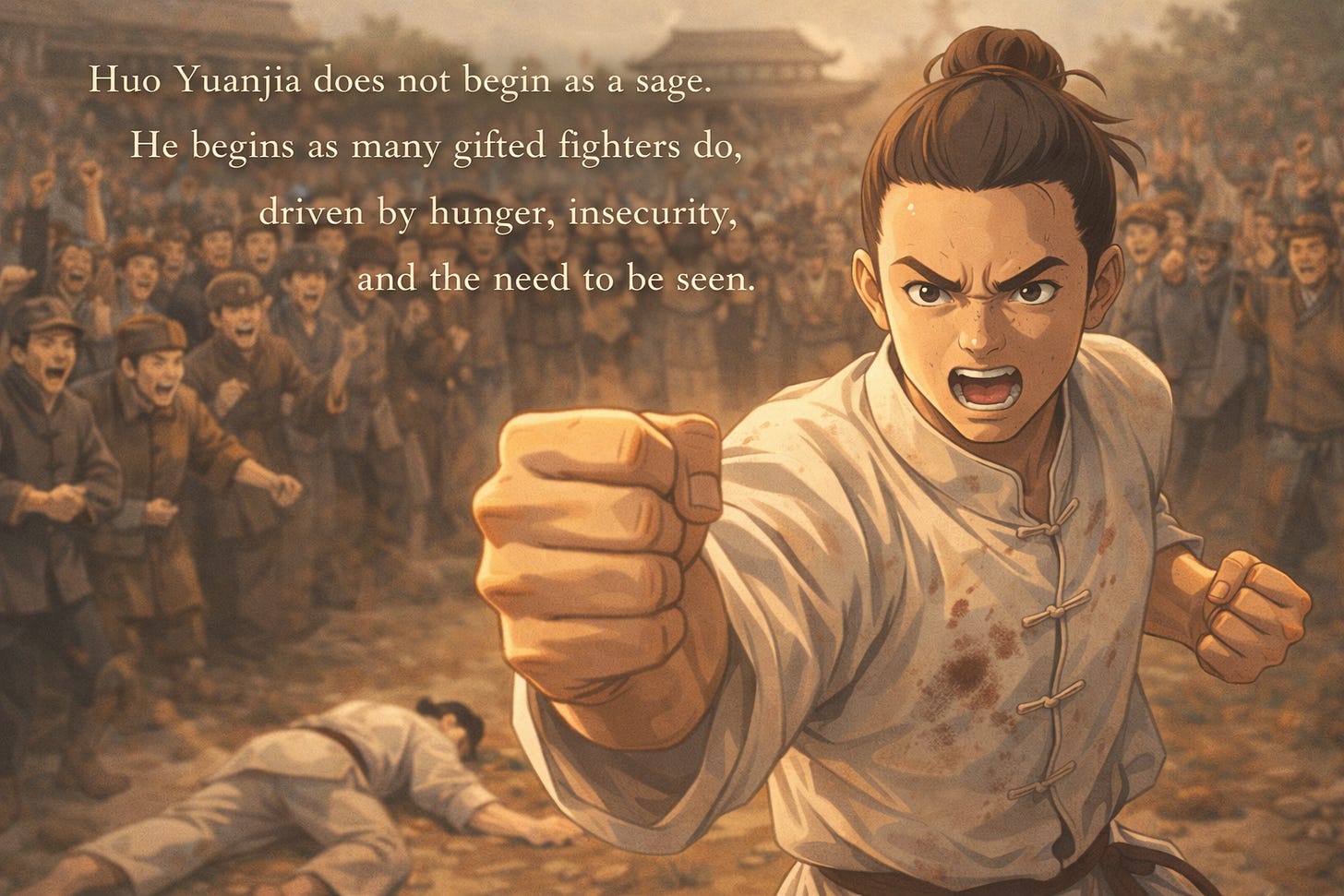

Huo Yuanjia does not begin as a sage.

He begins as many gifted fighters do, driven by hunger, insecurity, and the need to be seen.

In his early victories, dominance is mistaken for strength, and applause for purpose. Each fight expands his reputation while quietly eroding his center. His skill sharpens, but his inner life contracts. He is undefeated and already losing something essential.

This is the first trap of martial excellence.

When the art stops cultivating the practitioner and starts reflecting the ego back to itself.

Traditional martial culture understood this risk. It placed a boundary around power, not to weaken it, but to prevent it from turning inward.

Without that boundary, excellence outruns integration.

Combat Sports and the Erosion of Wu De

Modern combat sports increasingly reward a narrow definition of success: winning, dominance, visibility, reputation, the monetization of identity.

At first, this feels empowering. Results silence doubt. Recognition feels like arrival.

But something subtle shifts.

When victory becomes identity, the nervous system never rests.

When reputation becomes oxygen, silence feels like extinction.

When meaning is outsourced to applause, loss becomes annihilation.

This is anti Wu De.

Not because competition is wrong, but because self command is replaced by self consumption.

Skill begins to grow faster than wisdom can integrate it.

Intensity replaces alignment.

Striving replaces cultivation.

Eventually, the system turns inward.

And it collapses.

Fearless and the Return to the Ordinary

The power of Fearless is not in its fights, but in its restraint.

Huo’s tragedy does not arrive as injustice alone, but as consequence. The violence he used to define himself returns, magnified. What shatters him is not merely loss, but recognition. Recognition that skill without virtue is unstable, and power without wisdom invites ruin.

So he disappears.

Not to train harder.

Not to plot revenge.

Not to seek more glory.

But to become ordinary.

He labors in fields. Learns patience from seasons. Eats simply. Listens more than he speaks. In this quiet life, martial arts cease to be something he performs and become something he embodies. Strength re-enters his body not as force, but as alignment.

This is where Daoism enters his soul.

True power does not rush forward. It arrives when resistance ends. Movements become smaller. Intent softer. Outcomes less important. He no longer fights the world. He flows with it.

And in this emptying, something Buddhist takes root.

He stops clinging to victory. He stops defining himself through identity. The fighter who returns to Shanghai is not the man who left. That man has already died.

This return to the ordinary is not retreat.

It is transcendence.

As the poem says, striving for the extraordinary may look admirable, but it is the way of foolishness.

The ordinary is where Huo’s martial virtue is awakened.

Martial Virtue Awakened

When Huo returns to the public stage, he does not return to entertain.

He returns to restore meaning.

Fighting is no longer spectacle. It becomes expression.

Each exchange carries restraint.

Each bow carries respect.

Each refusal to humiliate an opponent carries compassion.

Mercy, benevolence, dignity.

This is Wu De.

His final fight is not about winning, nor even about China defeating any foreign powers. It is about showing that dignity does not require domination, and that courage can exist without hatred.

Knowing death is inevitable, Huo chooses Wu De over survival.

In doing so, he reveals the highest expression of martial arts.

A body capable of violence, governed by wisdom.

A spirit capable of victory, freed from attachment.

Huo Yuanjia does not transcend martial arts by abandoning fighting.

He transcends fighting by governing it with martial virtue.

Wisdom He Could Not Understand Until the End

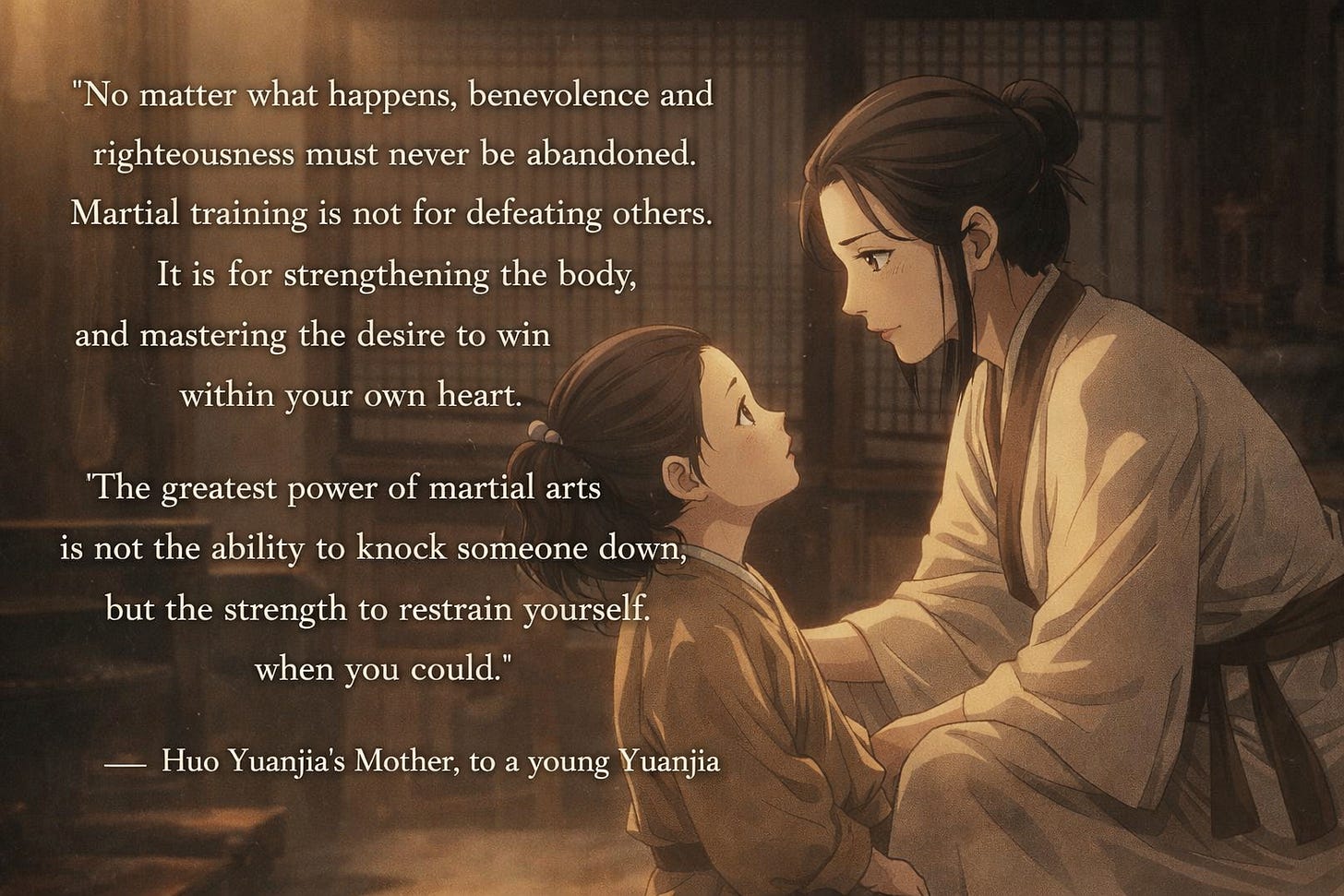

At the beginning of Fearless, before Huo Yuanjia has become feared or celebrated, his mother speaks to him with a clarity that the boy cannot yet receive.

She tells him that martial practice is not meant for defeating others.

It is meant for self cultivation and protection.

Martial arts exist to strengthen the body so that one may help others, not to make trouble, not to seek revenge, not to dominate or humiliate. Their true purpose is to overcome one’s own impulses toward arrogance, anger, and the hunger to be admired.

She reminds him that benevolence and justice, ren and yi, must never be separated from the Dao and from de. Skill without virtue is empty. Strength without restraint is dangerous.

To live harmoniously with others, she tells him, one must learn respect and compassion. That is what earns true regard. Fear is not the same as respect.

Being feared is easy. Being respected requires character.

Huo hears these words.

But he does not yet understand them.

To a young fighter burning with ambition, restraint sounds like limitation. Compassion sounds like weakness.

Self cultivation sounds abstract compared to the immediate proof of victory.

So he does what many gifted practitioners do.

He outruns the wisdom meant to guide him.

Everything that follows in Fearless is not a discovery of new truth, but a long and painful return to this original teaching. Huo spends his life learning through consequence what his mother already knew through understanding.

When he finally embodies Wu De, it is not because he has surpassed his parents’ wisdom, but because he has suffered enough to arrive back at it.

This is one of the film’s quietest and most devastating insights.

The deepest truths of martial virtue are often given early.

They are not ignored because they are false, but because the one hearing them is not yet able to receive them.

The Lesson Completed

There is another quiet scene early in Fearless whose weight is only revealed at the end.

As a boy, Huo Yuanjia watches his father compete in a decisive match. The stakes are clear. Victory would establish unquestioned supremacy. The opportunity to finish the opponent is there.

And yet his father does not take it.

He restrains himself. He chooses not to press the advantage. He understands that to win completely would be to harm unnecessarily, to let dominance eclipse martial virtue.

To the crowd, this looks like weakness.

To young Huo, it looks like failure.

The moment burns into him not as wisdom, but as prohibition. His father’s restraint feels like a denial of greatness. It becomes the seed of Huo’s later obsession. He will not hesitate. He will not hold back. He will become what his father refused to be.

For years, Huo mistakes excess for courage and finishing an opponent for virtue. He proves himself through domination. He becomes feared, admired, undefeated. And in doing so, he runs directly past the lesson his father tried to embody.

Only at the end does the symmetry reveal itself.

In Huo’s final fight, he once again reaches the decisive moment. The opening is there. The finishing blow is available. One strike would secure unquestioned victory.

The crowd waits.

History waits.

And Huo pauses.

Knowing he is dying from getting poisoned, knowing the outcome no longer belongs to him, Huo refuses to let victory become cruelty. Even in his final moments, he could end the match decisively.

And he does not.

He governs himself where once he could not. He places martial virtue above outcome. He completes the gesture his father began decades earlier.

When the match ends and the decision is about to be announced, something unexpected happens. The opponent who was meant to be declared the victor raises Huo’s arms instead. The crowd responds instinctively. They do not cheer the result. They chant Huo’s name.

What the boy once rejected as weakness, the man now recognizes as the highest strength.

The father embodied it without explanation.

The son had to lose everything to understand it.

Huo does not complete his story with a strike.

He completes it with restraint.

That is martial virtue.

That is Wu De.

A Closing Note

Thank you for reading this first installment in my series on martial virtue.

If you are unfamiliar with my work, my name is Lawrence Kenshin. My path in martial arts began with the careful study of the greatest fighters of our time, first through analysis, and later through direct apprenticeship. That path eventually led me to become the final protégé of Dr. Michael Yessis, whose legendary work in sports science work reshaped how strength, movement, and transfer are understood.

From that lineage, I developed an innovative approach to training I call Sudden Transfer. Its aim is simple: to bridge preparation and expression, so that athleticism and technique appear when they are needed most. This work is transformational and has allowed me to train some of the most accomplished fighters of this generation, as well as founders and leaders of some of the world’s most influential companies.

This series reflects what I have learned across those disciplines: that true mastery is not only about becoming more capable, but about becoming more governed. Through the embodiment of martial spirit and martial virtue, I have seen high performers transform not just their craft, but every aspect of their lives.

If you wish to explore that path more deeply and work with me one-on-one, you may reach out at:

lawrence@legendarystriking.com

Future installments will continue this exploration of Wu De, Sudden Transfer, and the completion of the martial path.